A 21st-century enlightenment

All great discoveries begin as blasphemies, which are resisted by those with something to lose.

The fact that an opinion has been widely held is no evidence whatever that it is not utterly absurd; indeed, in view of the silliness of the majority of mankind, a widespread belief is more likely to be foolish than sensible. - Bertrand Russell

A story about Albert Einstein dates to his time at Princeton. It seems the great physicist had fallen into the habit of posing the same examination questions every year. Confronted by the Dean for his apparent laziness, Einstein explained that his questions were the same—but the answers kept changing. This story is doubtless apocryphal, yet it makes a vital point; science is always unfinished business. As they used to say on the old X-Files TV show, "The truth is out there," but we never quite get to it. Our knowledge is always provisional. The best we can hope to achieve from the advance of science is a closer and closer approximation to the truth.

Curiosity, independence of judgement, and scepticism are the drivers of scientific progress. Of the three, scepticism is the most powerful. As sociologist Robert Merton noted, "Most institutions demand unqualified faith; but … science makes scepticism a virtue." Questioning prevailing beliefs is the way scientists progressively deepen their understanding.

Scientific scepticism is different from mere disbelief. Any idea can be rejected no matter how much evidence exists to the contrary. Donald Trump claimed that exercise is bad for you and that asbestos "got a bad rap." Former South African President, Thabo Mbeki, rejected any connection between AIDS and HIV, which he considered a harmless virus. US Presidential candidate, Mike Huckabee, described evolution as "just another theory." Robert Kennedy Jr. believes that vaccines (not just the anti-covid variety) cause more harm than good. These opinions are not examples of scientific thinking. At best, they are a form of dogmatism, a stubborn clinging to a point-of-view while rejecting the vast preponderance of the evidence. At worst, the critics of science adopt an attitude of postmodern nihilism. Objective reality is an illusion, so the evidence is irrelevant, and one view is as good as another. Scientific inquiry is different. It employs a particular type of scepticism called constructive dissent.

Constructive dissent

In 1968, Lord (Eric) Ashby, Vice-Chancellor of Cambridge University, delivered an address to the Association of Commonwealth Universities in Sydney. In his speech, Ashby suggested that academics take an "oath" like the Hippocratic Oath once taken by doctors. This academic oath would describe researchers' values and ethics, including "the discipline of constructive dissent."

According to Ashby, constructive dissent "must shift the state of opinion about a subject in such a way that the experts concur." It is not enough to reject a connection between HIV and AIDS, condemn all vaccines or reject evolution. To make a valuable contribution to knowledge, dissenters must use their expertise and observations to convince experts in their field to change their views. Critics who have no expertise, make no observations, and do not even try to persuade experts, are pseudo-sceptics who carefully select bits of evidence to defend their preconceived positions.

The road toward scientific truth is neither straight nor smooth. Few scientists are capable of what the mathematician Henri Poincaré called "flawless reasoning." There are always unexpected twists and turns, which is why the answers to Einstein's questions keep changing. Still, history records many examples of how constructive dissent advances our understanding: Copernicus, Galileo, Pasteur, the list of scholars who struggled against various dogmas is long and glorious. One particularly moving story concerns a Hungarian doctor named Ignaz Semmelweis.

Disinfecting hands

Ignaz Semmelweis was an early 19th century obstetrician. His career was devoted to the care of mothers and babies. In Vienna, where he worked, he was troubled to find that one mother in 10 died of "childbed fever." Today, we know bacterial infections caused these deaths, but no one had heard of bacteria in Semmelweis' time. Pasteur's pioneering work was still decades in the future.

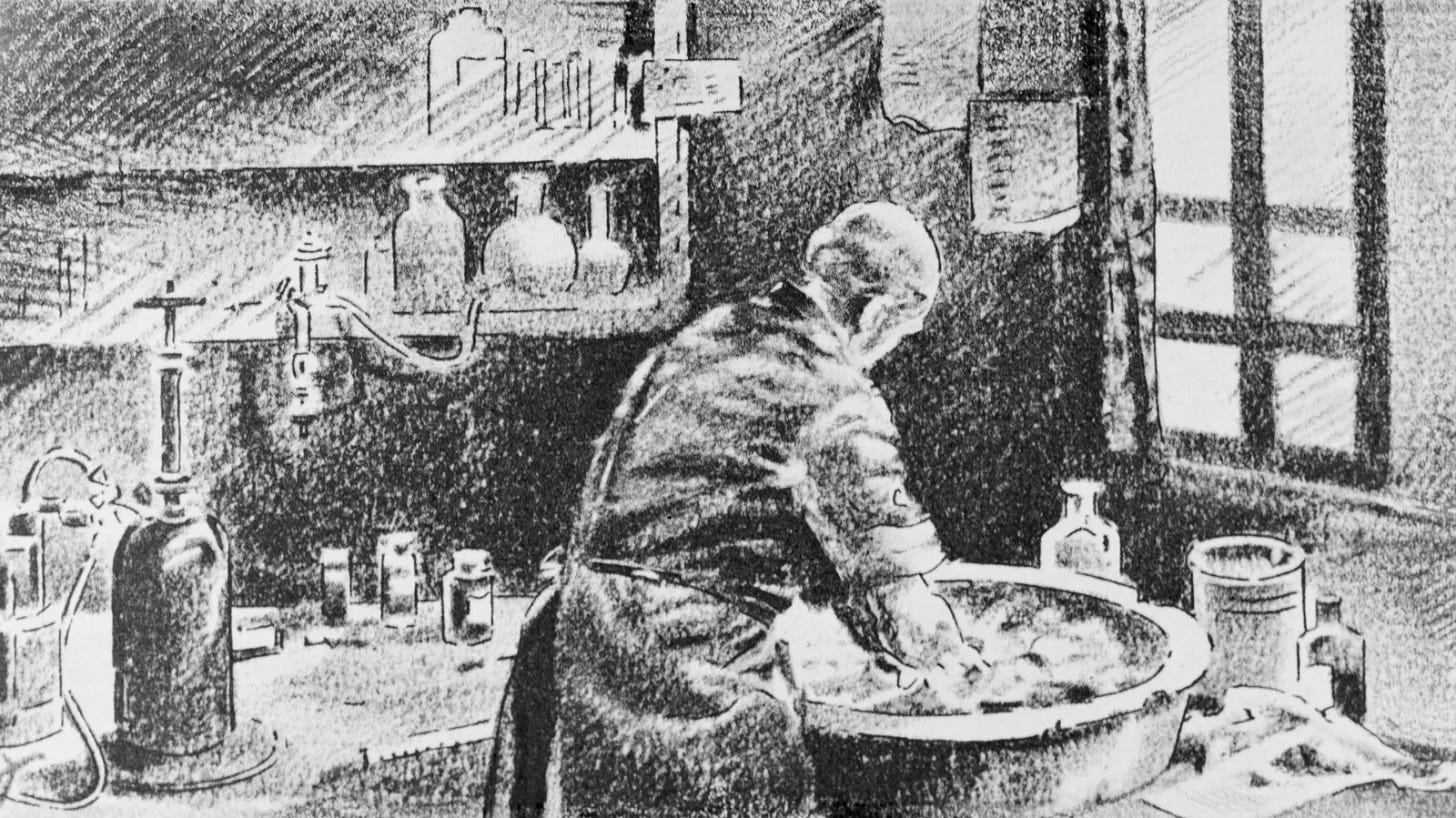

Semmelweis was a careful observer of hospital routines. He noticed that doctors often went directly from dissecting corpses in the morgue to examining mothers and delivering babies in the maternity ward. He wondered whether doctors were transferring disease from the cadavers to the mothers. Semmelweis asked the other doctors to wash their hands with a chlorine solution before touching the mothers to test this hypothesis.

Semmelweis' colleagues were not impressed. How could a nobody, not even Austrian, dare to suggest that his experienced colleagues are killing their patients? Anyway, most doctors washed their hands with soap and water when they left the dissecting room. Their hands looked clean when they entered the maternity ward. If there were something too small to see on their hands, it would surely be too small to cause the death of a mother during childbirth.

Semmelweis was undeterred. He continued to harangue the other doctors to disinfect their hands with a chlorine solution. Reluctantly, they complied, but they used Semmelweis' hand washing experiment as an opportunity to poke fun at him. The doctors made a show of lathering up, cleaning under their fingernails, joking and mocking Semmelweis's foreign accent. But the dying stopped. Getting doctors to disinfect their hands saved lives.

You might think Semmelweis had the last laugh, honoured by his profession and the people of Vienna for his lifesaving discovery. Alas, this is not what happened. Instead of praise, Semmelweis was forced out of the hospital and could not obtain another position in Austria. He returned to Hungary to take up work in a provincial hospital.

Semmelweis kept trying to convince people of the value of his ideas without success. Eventually, he decided that the only way to prove he was right was to infect himself. In the dissecting room, he stabbed himself in the palm of his hand with a scalpel he previously used on a cadaver. In line with his theory, Semmelweis developed a severe infection, which turned out to be fatal. Even his dramatic demise failed to change expert opinion. Semmelweis’ ideas were not generally accepted until twenty years later when Pasteur expounded the germ theory of disease.

The Semmelweis story reminds us that science is an enterprise to which people bring their intellectual strengths and the entire panoply of human flaws—pride, greed, vanity, and self-deception. Anthropologist Marshall Sahlins summarised the scientific process succinctly as "the pursuit of disinterested knowledge by self-interested people."

There is nothing wrong with enlightened self-interest. It works well for the economy, and it usually works well for science. Competition among scientists means that science eventually transcends the imperfections of even its most flawed practitioners. What is troubling is how long it can take to change experts’ minds. To quote Poincaré again, we either "doubt everything or believe everything" when nuanced reflection is required. Consider the following story from my former university.

Understanding ulcers

I was once Executive Dean of Medicine at the University of Western Australia in Perth. In the 1980s, one of the pathologists at Royal Perth Hospital, Robin Warren, became interested in unusual bacteria that he claimed live in the stomachs of ulcer patients. He believed these bacteria could be responsible for some duodenal and gastric ulcers. Few doctors or researchers took Warren seriously because the dominant view at the time was that bacteria could not live in the acidic environment of the stomach. Anyway, everyone knew that stress, spicy foods, and aspirin caused ulcers.

One person who did take Warren seriously was a young doctor called Barry Marshall. Barry came from a working-class family and lived in a house with a dirt floor and outdoor toilet. He supported himself through medical school by harvesting wheat. Not an establishment figure himself, Marshall was drawn to Warren's iconoclastic work. He and Warren tried several times to culture stomach bacteria in the laboratory without success. Then, by a happy accident, laboratory staff, anxious to start their long Easter break, neglected to wash the stomach contents from their Petri dishes. After the holiday, Marshall and Warren found bacteria busily multiplying when they returned to work.

They identified the bacteria as a genus called helicobacter pylori. Warren and Marshall believed that helicobacter was responsible for some, perhaps most, ulcers. Hardly anyone agreed. Marshall thought he could sway expert opinion by showing a direct connection between the bacteria and gastric disease. So, like Semmelweis, Marshall decided to infect himself. He swallowed a solution containing helicobacter pylori. About a week later, he developed a severe case of gastritis. (Fortunately, not fatal.)

Marshall's dramatic demonstration failed to move medical opinion, at least not right away. As Semmelweis found, entrenched beliefs are difficult to change. No one likes admitting they are wrong, and there are always vested interests. For example, antacid medications, the most common ulcer treatment, were highly profitable products for pharmaceutical companies. Drug company representatives spent considerable time and money finding flaws in Marshall and Warren's work to protect their market. They argued strongly for the continuation of antacid treatments (which remain big sellers, even today). It took ten years before the American National Institutes of Health agreed that eliminating helicobacter pylori would cure many types of ulcers. In 2005, Marshall and Warren won the Nobel Prize in Medicine for their contribution to science and the alleviation of human suffering.

The stories of childbirth fever and helicobacter pylori illustrates the power of constructive dissent, but they also highlight a crucial point about science. All great discoveries begin as blasphemies, which are resisted by those with something to lose.

Of course, resistance is not always futile or wrong. Sometimes, new "discoveries" turn out not to be discoveries at all. Such was the fate of René Blondlot.

Self-delusion

Prosper-René Blondlot was a turn-of-the-20th-century French physicist who claimed to have discovered a new type of radiation. He called his discovery the N-ray after Nancy, where he lived. Many other French scientists confirmed his observations. In contrast, physicists in other countries were unable to see N-rays. When the scientific journal, Nature, sent an American researcher to France to settle the question, it soon became apparent that N-rays did not exist. Blondlot was not a deliberate fraud; his very human wish to be well-regarded led him to deceive himself. Ironically, the more famous Blondlot became, the easier it became for other French physicists to confirm his findings. Blondlot's self-delusion became contagious.

Even renowned scientists can be deluded. In March 1989, the University of Utah held a press conference to announce that two faculty chemists, Stanley Pons and Martin Fleischmann, had discovered a non-polluting source of energy they called "cold fusion." The university leaked the story to The Wall Street Journal, which splashed it across the front page and followed it up over the succeeding weeks. The claim was big news because it promised an endless supply of cheap and clean energy. Pons was a well-published scientist, and Fleischmann was a Fellow of the prestigious Royal Society; other scientists had to take their claim seriously.

Curiously, for such establishment figures, Pons and Fleischmann flouted the usual academic conventions. They went directly to the media without making the details of their work available to other scientists for replication. Physicists were forced to guess about the methods used in the Pons and Fleischmann experiment to replicate the cold fusion. When preliminary results started to come in, they were largely negative. Pons and Fleischmann dismissed these studies; researchers used the wrong techniques or materials, did not wait long enough, and their methods were sloppy.

The Utah legislature appropriated $5 million for the university to commercialise cold fusion. Orchestrated by public relations consultants hired by the university, a congressional hearing was held in Washington to laud the discovery and appropriate even more money so that America could commercialise the technology "before the Japanese" (which seems a rather quaint fear today).

Nothing came of any of this. The entire episode was created by sensationalist media, a university desperate for prestige, and gullible politicians. Incredibly, although no new evidence has been presented over the decades to show that cold fusion exists, many scientists still believe it does. Blondlot went to his grave, still believing in the existence of N-Rays. Self-deception is difficult to dislodge.

A 21st century enlightenment

The discipline of constructive dissent relies on the cardinal virtues of the Enlightenment: rationality, reason, and empiricism. These virtues are constantly under threat. Consider Prince Charles's remarks:

It might be time to think again and review it [the Enlightenment] and question whether it is effective in today's conditions, faced as we are with enormous challenges all over the world. It must be apparent to people deep down that we have to do something about it.

We cannot go on like this, just imagining that the principles of the Enlightenment still apply now. I don't believe they do.

Others share Charles' views. For example, academics in New Zealand recently claimed that indigenous creation myths are just as valid a description of how the world works as physics. Such views underline the pressing need to reinvigorate the Enlightenment for the 21st Century.

Like the Enlightenment, constructive dissent is essentially a mindset, a way of thinking about the universe and our place in it. It provides an objective way to collect facts, assess them, test hypotheses, and ensure intelligent debate. Practitioners of constructive dissent accept the provisional nature of our understanding and keep their minds open to other possibilities. Most of all, constructive dissent is a form of optimism because its practitioners believe that, with deeper understanding, the future can be better than the past—and what could be more optimistic than that?

A version of this article formed part of a seminar, Science, Scepticism and the Future, held at a meeting of the Mont Pelerin Society.

Jonathan Swift: "When a true genius appears in the world, you may know him by this sign, that the dunces are all in confederacy against him."