Between Patience and Fortitude

In an age of noise and urgency, the library is a quiet kind of miracle.

My first real job was at the New York Public Library—the one with two lions guarding the doors.

Every day, I passed between them—those silent guardians of Fifth Avenue, carved from Tennessee marble, calm amid the city's cacophony. Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia named the lions Patience and Fortitude, virtues he believed New Yorkers would need to survive the Great Depression of the 1930s. I’m not sure the citizenry always lives up to these ideals, but the lions wear their names with quiet dignity, giving visitors something to strive for.

In those long-ago days, Bryant Park—just behind the library—was not the manicured oasis it is today. It had a reputation for drugs, loiterers, and the kind of urban weariness that made you walk a little faster. Today, it is home to flower beds, book markets, chess tables, summer movies, and even an ice rink in winter. Back then, I gave it a wide berth. Instead of eating in the park, on lunch breaks, I’d stroll up Fifth Avenue, pausing at shop windows—Tiffany, Brooks Brothers, Saks—trying to imagine a future where such things were not entirely out of reach. But it was the library, not the luxury shops, that offered something lasting: a glimpse of what life might become, a place to read, think, and dream.

Inside, the library offered a kind of hush, not quite silence but something more inspiring—a shared reverence for the written word. Built in 1911 atop an old reservoir, the library was then the largest marble structure in the country. Its classical columns and elaborate ceilings were designed to elevate both architecture and aspiration. Its enormous reading room has been home to generations of students, scholars, and other seekers of wisdom.

I worked in the theatre collection, then housed high in the building, where time hung in the air with the imagined smell of old playbills and greasepaint. We had every Broadway programme ever printed. Ageing actors—names long vanished from marquees—would climb the stairs to confirm their performance records, hoping they'd crossed the threshold to earn a decent union pension. Often, they came to reminisce. They’d lean on the reference counter and swap stories: the night the curtain jammed, the understudy who rose to stardom, the sandwich they ate before a matinee.

The library was a repository of theatrical history. We had scripts, prompt books, costume sketches, and publicity stills. Later, when the collection moved to Lincoln Center, actors’ costumes were also displayed. The collection was an invaluable resource for actors, directors, and set designers seeking inspiration for a new production and a treasure trove for scholars who spent their lives in thrall to the theatre.

My job was humble: I fetched requests from the stacks housed underground and sent them to the reading room via a pneumatic tube system. When I was late for work, which wasn’t rare, I’d be assigned to “read the shelves,” a euphemism for checking that books were correctly ordered. This was tolerable in most sections, but a form of bibliographic penance in the music collection, where the scores were thin, numerous, and fond of slipping out of place.

And yet, I loved it. I loved all of it. I loved the quiet, the unspoken rules, the sense that I was part of something enduring. Libraries asked nothing of me but attention. I entered university at sixteen intending to study English literature. The library prepared me for what that meant: following a trail of words through time and trusting that somewhere, buried in all the pages, I might find myself.

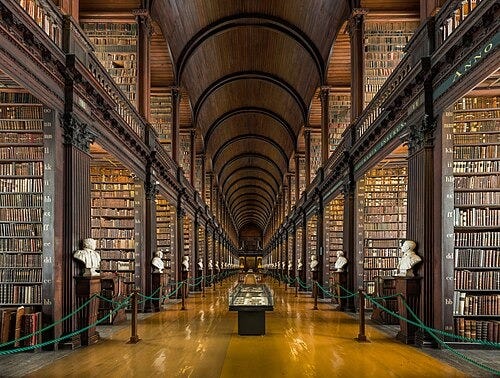

As it turned out, my career took a different turn. Still, I remained under the spell of libraries. I have haunted them all over the world. In London, I sat under the dome of the British Library watching scholars shuffle silently across the floor. In Paris, the Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève drew me in with its latticed iron galleries and golden glow. In Dublin, I stood beneath the barrel-vaulted Long Room at Trinity College and lost myself in its astonishing beauty.

Later, as Vice-Chancellor and President of Macquarie University in Sydney, I helped design and build Australia’s first automated library. The robots that “read” the shelves and retrieved books were far more accurate and much faster than I ever was.

There were plenty of critics. I was told libraries were passé. Books were going digital. Knowledge is all in the cloud. But students kept coming, and they still do. They come to think, to talk, to be together. They come because, despite the best efforts of modernity, the library endures.

And rightly so. A library is not just a warehouse for books. It is an assertion of public spirit. It is a school for the self-taught, a refuge for the misfit, a parliament of ideas where no one needs to raise their voice. Andrew Carnegie understood this. He founded more than 2,500 libraries across the English-speaking world, believing that access to books could lift lives that society had left behind. The Sarajevo library continued lending books even as the city was under siege. The American Library in Paris provided a home (and a delivery service) for books banned by the Nazis. Libraries do not close when things fall apart—they open.

Frederick Wiseman’s magnificent documentary, Ex Libris, captures the New York Public Library in this spirit: not as a relic, but as a living institution. We see librarians tutoring children, helping job-seekers, and answering questions that stump Google. At one point, a staff member explains how the library helps immigrants adjust to life in New York, teaching them English through poetry. The film is three and a half hours of understated civic heroism.

As Susan Orlean writes in The Library Book, “All the things that are wrong in the world seem conquered by a library’s simple unspoken promise: Here I am, please tell me your story; here is my story, please listen.” A library does just that—it listens. It doesn’t interrupt, it doesn’t sell or scold. It simply holds open a space for you to think, to learn, or just to be. That, in an age of noise and urgency, is a quiet kind of miracle.

Libraries have changed, yes—there are cafes now, discussion spaces, and digital terminals—but their function is unchanged. They remain the last truly democratic places in public life: open to all, asking nothing but your curiosity. They are also, increasingly, the last spaces where we are not being watched, tracked, sold to, or entertained by monolithic technology companies. Libraries are repositories not just of books, but of judgement, an institution that knows the difference between knowledge and nonsense.

Libraries have inspired fiction and dramas: The Name of the Rose, with its murderous labyrinth of forbidden books; The Breakfast Club, where five teenagers meet not in detention but in self-discovery; and even Doctor Who, where an entire episode is set inside a planet-sized library. The metaphor is always the same: the library represents a defence against forgetting.

And perhaps that is the most enduring magic of the library: it holds not only what we know, but all that we long to understand. It is a living archive, and an invitation to imagine more. As Alberto Manguel writes in The Library at Night, “Every bookshelf suggests the limits of what we know. The empty spaces between the titles are the dreams we haven’t yet dreamed.”

Libraries have shaped me more than any classroom. They remain, to me, among the highest expressions of civilisation. I began my working life in a library. If I’m lucky, I’ll end it in one too—still reading, with patience and fortitude.

Postscript

This article is a tribute not only to libraries, but to the people who make them possible—the librarians, archivists, shelvers, cataloguers, restorers, and quiet guides who keep the lights on and the doors open. In an age addicted to speed and spectacle, they preserve spaces for patience and thought. Their work rarely makes headlines, but without them, the rest of us would be lost in the noise.

I'm a member of multiple libraries, but the NSW State one is my happy, happy place and echoes (quietly, of course, so as not to disturb anybody) the joys you found in NY.

Thanks for another fantastic read Steven. Beautifully written - heartfelt and honest and incredibly evocative.