The Age of Bullshit

In a world of “frameworks,” “stakeholders,” and “outcomes,” public language is losing its grip on meaning.

Everything that can be thought at all can be thought clearly. Everything that can be said can be said clearly.

―Ludwig Wittgenstein, Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus

When Princeton professor of philosophy Harry Frankfurt published his celebrated book, On Bullshit, he gave a certain pungent Anglo-Saxonism its intellectual debut. Until then, the term had largely been confined to bar stools, schoolyards, and frustrated dinner conversations. Frankfurt’s achievement was to locate a moral and philosophical distinction: bullshit, he said, is not the same as lying. The liar knows the truth and seeks to conceal it. The bullshitter, by contrast, is indifferent to the truth altogether. His (or her) concern is not to mislead, but to impress.

This, it turns out, is an indispensable insight into the modern condition.

Public language today is riddled with what might charitably be called bullshit. It is a kind of lexical smog — phrases that hang in the air long after meaning has departed. Bullshit afflicts governments, corporations, universities, non-goverment organisations, and yes, media commentary itself. It is global, non-partisan, and not always well-intentioned. Bullshit speaks in the dialect of “stakeholders,” “frameworks,” and “outcomes.” It is allergic to verbs. It is addicted to means rather than ends. And it thrives where precision goes to die.

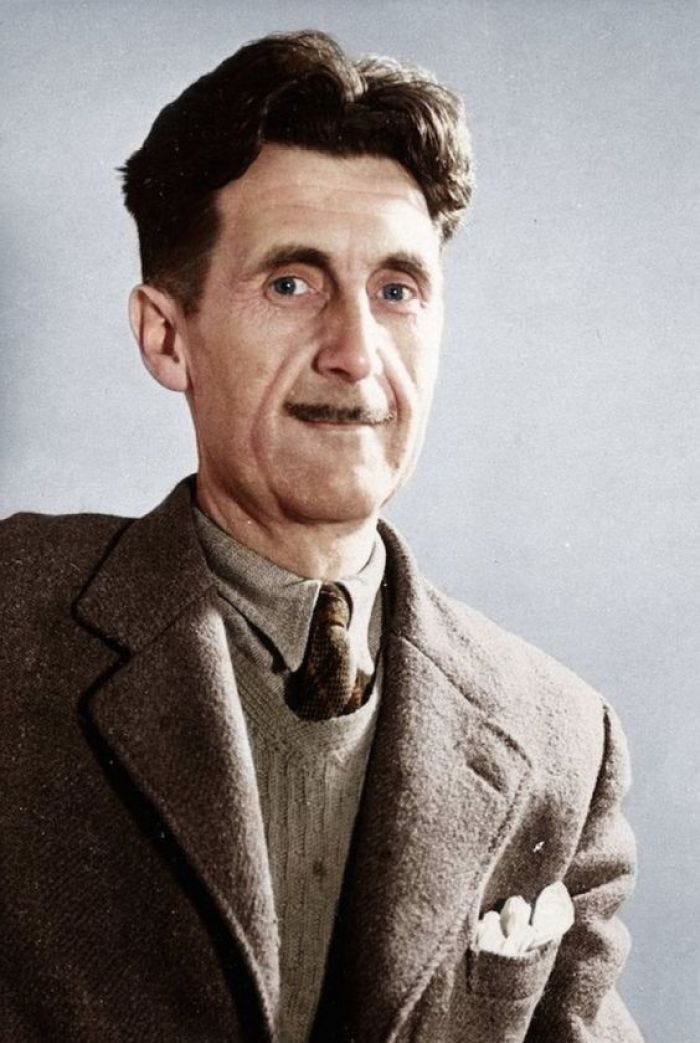

George Orwell, writing in 1946, saw it coming. In Politics and the English Language, he diagnosed how political language “is designed to make lies sound truthful and murder respectable, and to give an appearance of solidity to pure wind.” That was in the age of Stalinism and the British Empire. The phrase “collateral damage” had yet to be coined. No one had yet spoken of “engaging with key learnings.” The modern locutions are less brutal, but no less evasive.

Orwell was particularly attentive to how abstract language serves to obscure responsibility. Consider the passive voice: mistakes are made, structures are inadequate, lessons are being learned. No one is at fault. Everyone is participating. The machine whirs on.

Today's equivalent is the managerial gerund. Governments do not do; they are “delivering.” Companies are not making profits; they are “enhancing shareholder value.” A failure is “an opportunity for systems improvement.” A scandal becomes “a moment for reflection.” The aim, invariably, is to sound as if something is happening, preferably in a way that defers accountability until the matter is forgotten.

It is no accident that meaningless linguistic constructions flourish in technocratic environments. The language of modern public life borrows liberally from business schools, consultancy firms, and HR departments — institutions whose primary outputs are meetings and documents. Here, we “pivot”, “leverage”, and “co-create.” We don’t say what we think; we “surface perspectives.” Nothing is ever wrong, only “sub-optimal.” The goal is not clarity but defensibility — a form of lexical risk management.

The philosopher J.L. Austin, whose work on speech acts still underpins modern linguistics, argued that language is not merely descriptive but performative. To say something is, in many contexts, to do something. If I say “I apologise,” I have not merely reported my remorse; I have enacted it. Bullshit operates on this same principle but with diminished stakes: it is the simulation of performance. It gestures at seriousness without committing to it.

Take, for example, the phrase “We’re committed to evidence-based policy.” A noble idea. But what follows is often a cascade of jargon-laden initiatives — “multi-stakeholder consultations,” “capability reviews,” “robust evaluative mechanisms” — in which the evidence is both amorphous and oddly beside the point. The phrase becomes a talisman, not a method.

Or consider climate change, which in language terms has evolved from denial to euphemism. We are now in an age of “net-zero pathways,” “technology-neutral transitions,” and “decarbonisation opportunities.” The Earth may be warming, but our prose remains stone-cold dead.

Artificial intelligence presents a more recent case. Policymakers solemnly declare the need for “responsible AI frameworks” and “ethical guardrails,” while simultaneously investing in autonomous weapons systems and surveillance platforms. Here again, the language obscures the underlying tension: we wish to appear cautious while moving rapidly. The result is language that accelerates nothing and clarifies less.

Writers from Orwell to former Czech president Václav Havel have warned of the soul-eroding effects of such language. Havel, writing under Communist rule, saw the state’s reliance on ritualised slogans as a way of enforcing conformity. To refuse to repeat the official phrases was an act of resistance. Today’s bullshit is less coercive but no less insidious. It lulls rather than frightens. It flatters rather than threatens. But it asks of us the same thing: a suspension of disbelief.

This is not to suggest that all bureaucratic language is inherently dishonest. Nor is it to sneer at the complexity of governing modern societies. Public life does involve compromises, consultations, trade-offs, and a fair bit of administration. But complexity does not excuse opacity. As Orwell put it, “the great enemy of clear language is insincerity.”

The real problem with bullshit is that it becomes self-replicating. When everyone speaks it, it becomes the expected register. Speaking plainly becomes a risk. Clarity sounds naïve. Precision seems rude. And so the system sustains itself — not through conspiracy, but through habit.

What, then, is to be done?

The answer, if there is one, is not cynicism. The cynic shrugs and says, “That’s just how things are.” The sceptic, by contrast, asks questions. He reads the report and asks what, precisely, is being said. He hears the minister speak of “resilience frameworks” and asks: for whom? To what end? How will we know if it has worked?

This kind of questioning is difficult. It slows things down. It produces fewer headlines. But it is also the only known antidote to bullshit.

In the end, public language shapes public thought. It determines not only what we say, but what we notice. A society fluent in bullshit becomes slowly deaf to urgency, blind to fraud, and numb to failure. It stops expecting clarity, and then forgets how to provide it.

Frankfurt warned that bullshit undermines our relationship to reality. Orwell warned that it makes thinking itself difficult. Both were right. And so the next time you hear someone “leaning in” to a “whole-of-system innovation dialogue,” try asking a simple question: what are they actually doing? If the answer is elusive, you may be hearing the sound of something being said just to make an impression — the hum of public life in the age of bullshit.

Brilliant. This is the language of "Yes Minister". The problem is that government is not a TV comedy. Peoples lives are adversely affected by this bullshit. "Net zero" and "inclusion" are quintessential examples

Doubleplusgood.