We pretend to teach, and students pretend to learn

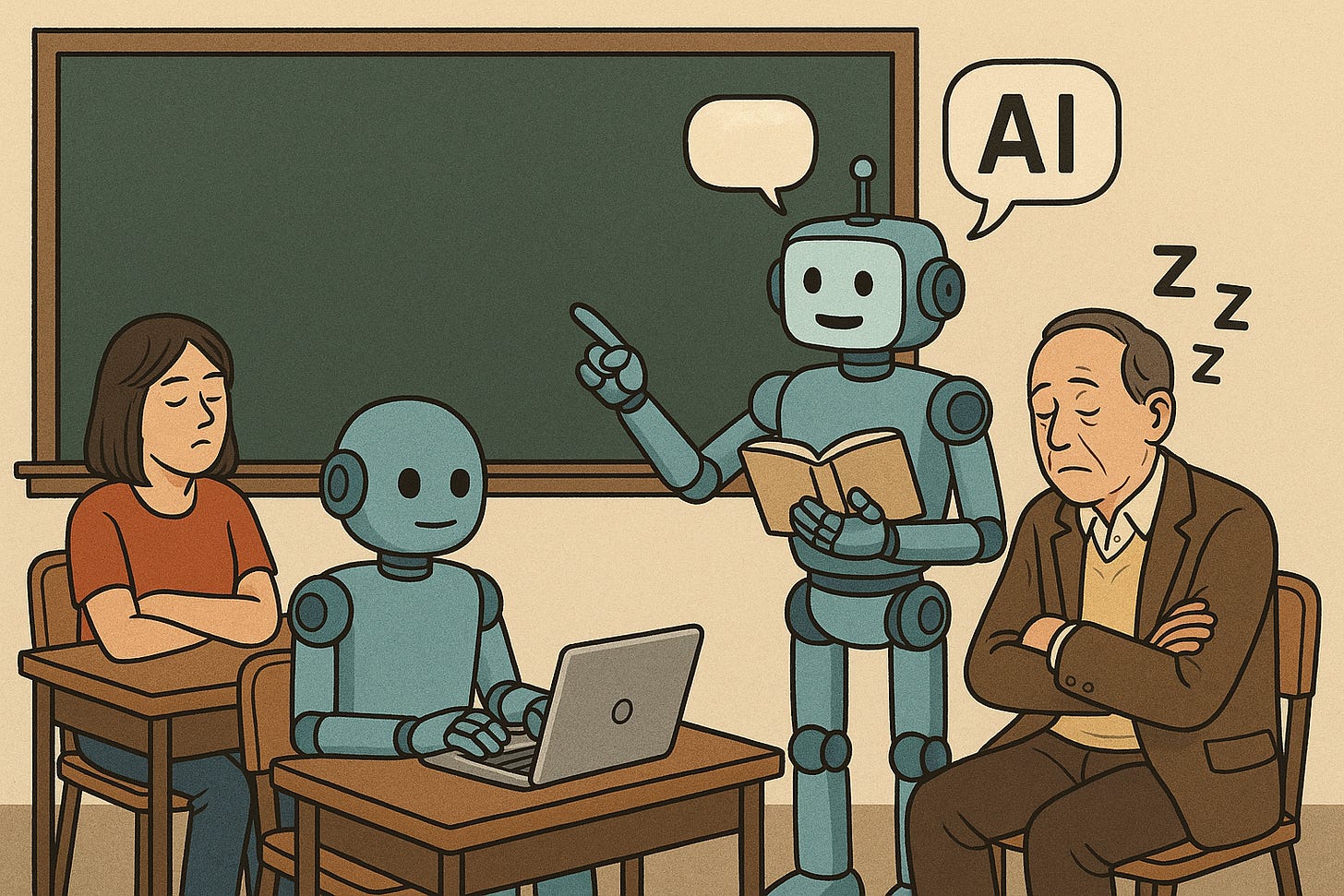

In our brave new AI world, academics pretend to teach, students pretend to learn and administrators pretend it all adds up to something called higher education.

According to a recent survey by the UK Higher Education Policy Institute, 92% of university students use generative AI in some form, and 88% admit to using it to produce their assignments. Large numbers of AI users have also been reported in the USA and Australia. This is why AI chatbot usage plummets during the summer break and soars again when classes resume.

And it’s not just students relying on AI; the New York Times reports that professors are using chatbots to write papers, produce lecture notes and mark assignments. The result is a perfect closed system. AI creates exam questions, writes student essays, grades them, and then uses feedback to improve its essays. (No wonder grades are inflating.)

To combat cheating, professors have enlisted AI chatbots to identify students who use them, while students are becoming increasingly sophisticated at avoiding detection. They consult multiple chatbots, combining their output into something “original”. They sprinkle their papers with grammatical and spelling errors to make their work appear more human.

The monumental absurdity of this situation recalls a joke from the old Soviet Union. Workers described their economic system as simple: “We pretend to work, and they pretend to pay us.” Paraphrased for our universities, the saying might go, “We pretend to teach, and students pretend to learn.” Degrees, essays, lectures, and PowerPoints provide the illusion of learning while AI does all the heavy lifting.

How many graduates could pass an independent test of what they are supposed to have learned? For that matter, how many academics could? When Australia introduced a literacy and numeracy test for would-be schoolteachers (LANTITE), many failed. If the teachers charged with educating the next generation can’t spell or add up, what hope is there for their pupils?

To rescue higher education from total AI takeover, some nostalgic souls propose a return to handwritten examinations, pens and copy books. This might work for mathematics and other subjects where multiple-choice or short-answer exams can be used to assess mastery of the material. The humanities and arts, however, rely on long-form writing—essays, themes and term papers—to assess understanding. They will find it impossible to revive handwritten examinations because university students can no longer write longhand. The Australian National Curriculum requires students to learn cursive writing, but schools ignore the requirement because handwriting isn’t tested in national assessments. As a result, most undergraduates can neither write nor read cursive. They have been cheated of a useful tool. A written exam would take days as students laboriously printed each letter like medieval monks illuminating a manuscript

Some teachers have already given up. They say AI should be “taught” as a tool for the future, thereby turning plagiarism into pedagogy. We heard the same argument when calculators arrived, and now few school-leavers can add or subtract unaided. I recently tried to buy a $5 coffee and $1 biscuit and was charged $16 because “that’s what the calculator said.”

The deeper problem isn’t technology. It is education’s purpose. Education has become a process rather than a pursuit—a system designed to issue credentials rather than create knowledge. Students enrol for the ticket, not the transformation. Academics, drowning in administrative tedium and research metrics, are struggling to hang on to the intellectual joy that makes universities worth defending. One by one, they are falling by the wayside. Soon, everyone will just be going through the motions.

Which raises an awkward question: if everyone is pretending, why not drop the act? Why hang around for three or four years when your assignments can be churned out by an algorithm in minutes? The traditional university model, built on the idea that a degree represents hard-earned knowledge, is turning into an expensive, time-wasting charade.

When AI becomes ubiquitous, taking on the role of both teacher and student—setting assignments and marking papers—it will be possible to pass a course without learning anything at all. We will have reached the apex of credentialism. Universities could streamline the whole process by simply selling degrees outright: fast-tracked, fully automated, parchment optional. Platinum packages could guarantee high honours. Employers would have their useless certificate, and institutions could devote themselves to what they have learned to do best; branding and property development.

Unfortunately, civilisation depends on passing real knowledge from one generation to the next, not on generating plausible imitations of education. AI can synthesise information, but it can’t seek the truth. It can mimic understanding, but it can’t care. And when a society forgets the difference between learning and performance, between a mind and a computer algorithm, the result isn’t progress; it’s parody.

Perhaps the saddest part of this story is the demoralisation of our academics. Soviet factories were famous for producing things nobody wanted, in quantities nobody could verify, to fulfil targets nobody believed in. Workers were strike-prone, cynical, and frustrated by their lack of agency. Today’s academics are in danger of finding themselves in a similar predicament: trudging on like Soviet workers fulfilling a Five-Year Plan documented by quality assurance forms, diversity statements, and learning outcomes. It’s getting increasingly difficult to call what universities do “education.”

Maybe, in a decade or two, we’ll look back and tell our own version of the Soviet joke: “Remember when students studied and professors taught?” Until then, we’ll keep pretending. Students will pretend to learn, professors will pretend to teach, and administrators will pretend it all adds up to something called a university.

The AI chatbots, at least, will be honest enough not to care.

AI scans materials and ideas that were produced in the past. Some sentences are true, some are false, and some are a little of both (half true). There are no guarantees that AI can distinguish the reliability of the "truthiness" of each statement that it encounters. (Of course most sentences are descriptive and make no claims as to "truth.") As for discovering new information or new ideas I am skeptical that AI can do it. Could AI come up with the theory of relativity as Einstein did? Other people might have but human thought has capabilities that neither we nor AI are capable of understanding. Quantum computers might do the math in a remarkably short length of time which could benefit our understanding of, say, protein folding. If that's part of AI then it would be good. But displacement of human workers by AI will lead to decay. And we don't know if AI will keep as humans around as pets.

Excellent, Steven. Absolutely spot on. Do you think the 'rot' commenced a long time ago, with the strong focus on the commercialisation of universities, rather than a focus of providing quality education to students who take pride in 'owning' their learning outcomes through authentic measurement of assessments? This of course requires a genuine desire to offer genuine education to genuine students who are prepared to spend the hard yards of genuinely learning.