The world is turning classical

The world is turning classical. Not everywhere. Not all at once. But unmistakably - and just in time.

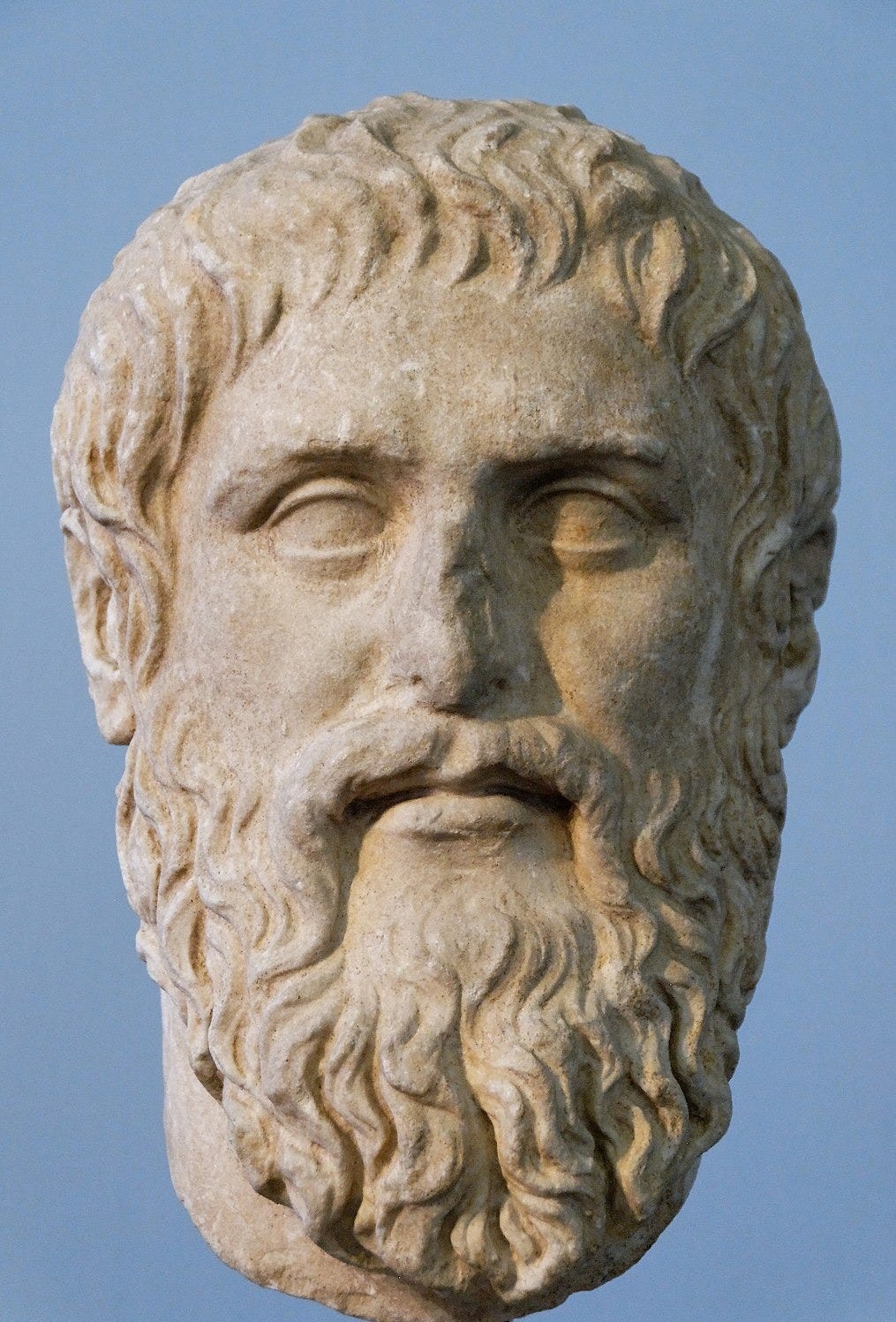

The object of education is to teach us to love what is beautiful.

— Plato, Republic, Book III

We are living through a quiet revolution. You won’t hear it shouted from the rooftops. You’ll find it in a room where a child is reading Homer aloud. You’ll glimpse it in a teacher guiding students through a Socratic dialogue. You’ll feel it in schools where poetry still matters, where words are loved, and where truth is not an embarrassment. Across the world, the classical education movement is gaining momentum.

Last year, at the annual Christopher Dawson Centre Symposium in Hobart, I spoke of how Australia is standing at a cultural crossroads. The values that have long underpinned our nation are not merely being questioned but, in many quarters, outright rejected. Yet, amid the disquiet and uncertainty, there remains a glimmer of hope - a hope that lies not in a blind clinging to the past, but in a thoughtful reaffirmation of the values that have shaped our shared history. Education once sought not just to inform students but to form them. That vision is returning, and Australia is joining in.

At the heart of our revival stands the Australian Classical Education Society (ACES). Born during the lockdown years, when the fragility of modern education was laid bare, ACES has become a rallying point for families, teachers, and thinkers seeking something enduring. Through conferences, curriculum work, and the cultivation of community, ACES is quietly rebuilding an education of substance.

The classical education movement has deep roots. From the earliest monastic schools to the great medieval universities, classical education was shaped by humanistic thought. It sought to harmonise faith and reason, scripture and Cicero, theology and the Trivium. Anselm’s fides quaerens intellectum - faith seeking understanding - was not just a slogan but a vocation. The aim was to form the whole person: intellect, character, and soul.

What began in Catholic schools has now found fertile ground across a wide landscape. Orthodox and Protestant communities have embraced it. Jewish schools are teaching Hebrew grammar and Greek logic alongside sacred texts. Even secular schools, longing for meaning, are joining the renaissance. The best of the classical tradition transcends any creed: it teaches students to read well, reason clearly, and live purposefully.

The results of the classical education movement are already visible. Campion College, Australia’s only tertiary liberal arts institution, continues to produce graduates who thrive in law, medicine, and the public square. New classical schools such as Hartford College in Sydney and the soon-to-open St John Henry Newman College in Brisbane are offering families what modern education has forgotten: an education anchored in wisdom, not fashion.

Globally, classical education is flourishing - from the dozens of Hillsdale-backed charter schools in the United States to independent academies in the UK, Uganda, and Brazil. They do not promise gadgets or gimmicks. They promise character formation and, sometimes, Latin homework (I can practically hear the sighs).

As classical education spreads at the school level, higher education remains the next great frontier. If we are forming students in the disciplines of logic, grammar, history, rhetoric, ethics, and natural philosophy, where will they go next?

Campion College has shown the way. Its success proves that a liberal arts university, rooted in classical principles, can thrive in Australia. But one college cannot serve a continent. We must begin to imagine what a broader classical tertiary landscape could look like. Perhaps a new honours program embedded within existing universities? Maybe a federation of classical teacher-training colleges? A new academic journal, or a graduate institute drawing talent from across the spectrum of religious and secular schools?

Whatever the form, we must ensure that students educated in the classical tradition do not find themselves marooned in a dreary postmodern university culture that denies the very truths they’ve been taught to seek. They deserve institutions as serious and humane as their schooling.

Yes, the classical movement is still a minority, but so was the early Renaissance. The movement’s strength lies not in numbers, but in depth. It dares to ask children to do difficult things - to memorise, to reason, to wonder. And they rise to the occasion. They always have. In an age of immediacy, classical education teaches the value of patience. In a time of identity politics, it teaches character. In a culture of noise, it focuses attention back on our strongest cultural roots.

As T.S. Eliot wrote in Little Gidding,

We shall not cease from exploration

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time.

The world is turning classical. Not everywhere. Not all at once. But unmistakably - and just in time.

I liked this article very much, but I guess I'm terribly biased! Thank you Steven.

I studied Classics, and still love it, so this would be music to my ears, but I’m less optimistic about it than you.